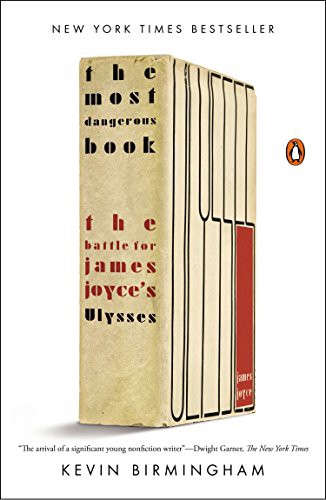

Björn recenserade The Most Dangerous Book av Kevin Birmingham

None

4 stjärnor

The Most Dangerous Book attempts something big, and to a large extent pulls it off. To tell not only the story of how James Joyce came to write Ulysses, his struggle to get it published in the face of critical and legal adversitities, and through that lens the story of how Victorian moralities and censorship laws were forced to make way for the modern(ist) world, never to be heard of again... uh, maybe.

Joyce's novel represented not a finished monument of high culture but an ongoing fight for freedom.

And as a pure biography of Ulysses and the soil it sprang from - Joyce's youth, the early modernist writers and the surrounding world of new political and literary ideas that weren't always always all that pleasant or peaceful, Joyce's love for Nora Barnacle, and the various unlikely characters who midwifed the novel (strikingly many of them women) - it's …

The Most Dangerous Book attempts something big, and to a large extent pulls it off. To tell not only the story of how James Joyce came to write Ulysses, his struggle to get it published in the face of critical and legal adversitities, and through that lens the story of how Victorian moralities and censorship laws were forced to make way for the modern(ist) world, never to be heard of again... uh, maybe.

Joyce's novel represented not a finished monument of high culture but an ongoing fight for freedom.

And as a pure biography of Ulysses and the soil it sprang from - Joyce's youth, the early modernist writers and the surrounding world of new political and literary ideas that weren't always always all that pleasant or peaceful, Joyce's love for Nora Barnacle, and the various unlikely characters who midwifed the novel (strikingly many of them women) - it's both well-researched and well written; at times thrilling, funny, heartbreaking. There are certainly more in-depth works on Ulysses as a work of literature, but that's not what Birmingham is going for here.

What's uncanny about censorship in a liberal society is that sooner or later the government's goal is not just to ban objectionable books. It is to act as if they don't exist. The bans themselves should, whenever possible, remain secret.

Because then you get to the big issue here - the one that gave the book its title. The actual question of just what feathers Ulysses ruffled, and how it could take more than 10 years for it to be legally published in most English-speaking countries. (Birmingham being American, the world is pretty much limited to the US, the UK, and Paris.) And I'm not saying these parts of the book aren't just as good; between the historical background on censorship laws and the ideas and methods that went into them back when postal workers were essentially Big Brother, the various attempts to get att what the hell "obscene" even means, and the minutiae of everything surrounding the troubled road to legality... It makes for a hell of a literary thriller, coupled with what is obviously a love for Ulysses itself, and I can't wait to re-read the damn tome again.

The legalization of Ulysses announced the transformation of a culture. A book that the American and British governments had burned en masse a few years earlier was now a modern classic, part of the heritage of Western civilization. Official approval of Ulysses, in prominent federal decisions and behind closed doors, indicated that the culture of the 1910s and 1920s - a culture of experimentation and radicalism, Dada and warfare, little magazines and birth control - was not an aberration. It had taken root. Or, more accurately, it indicated that rootedness itself was a fiction.(...) By sanctioning Ulysses, British and American authorities had, to some small but important degree, become philosophical anarchists. (...) There was no absolute authority, no singular vision for our society, no monolithic ideas towering over us.

Obviously the book could have done more - said more about modernism as a whole, continued to draw parallels to political developments past the publication of Ulysses, etc, but that's not the focus here, so that's fine. The main thing that irks me somewhat is that I feel like Birmingham tends to treat the central concept here, that of freedom of speech (well, print) just a tiny little bit too simplified; as if it was something you either have or don't have, and that it was entirely the work of Joyce and his cheerleaders that shepherded the world from one side to the other. Almost as if "Freedom" was a simple commodity, a word that means something in itself.

But eh, you can't have everything. Except of course by reading Ulysses.

...and the word that shakes it all down is YES.