The phrase "world literature" always bugged me. While it sounds broad enough, it's often used to mean "all that other literature that's not written in my country and/or the US/UK", often with the added implication (especially in connection with awards) that it's difficult, obscure, or at least exotic. For instance, when Le's The Boat came out and started piling up accolades, I remember reading an article that pointed to The Boat as an example of how all the good reviews in the world couldn't make a weird foreign book sell as much as Dan Brown.

Now, obviously very few authors regardless of nationality or critical acclaim sell as much as Dan Brown, so it's a pretty unfair comparison. But I still wonder if it would have occured to anyone to use this book, written in English by an Australian lawyer living in the US, as an example of weird foreign …

Granskningar och kommentarer

Den här länken öppnas i ett popup-fönster

Björn betygsatte The Battle of Brazil: 4 stjärnor

Northline av Willy Vlautin

"Fleeing Las Vegas and her abusive boyfriend, Allison Johnson moves to Reno, intent on making a new life for herself. …

Björn betygsatte At swim-two-birds: 4 stjärnor

Björn betygsatte The Enchantress of Florence: 3 stjärnor

The Enchantress of Florence av Salman Rushdie

A tall, yellow-haired, young European traveler calling himself "Mogor dell'Amore," the Mughal of Love, arrives at the court of the …

Björn betygsatte De fattiga i Lóđź: 4 stjärnor

De fattiga i Lóđź av Steve Sem-Sandberg

662 p. ; 23 cm

Björn betygsatte Thomas Mann, Der Tod in Venedig: 5 stjärnor

Thomas Mann, Der Tod in Venedig av Ehrhard Bahr (Erläuterungen und Dokumente)

None

3 stjärnor

The phrase "world literature" always bugged me. While it sounds broad enough, it's often used to mean "all that other literature that's not written in my country and/or the US/UK", often with the added implication (especially in connection with awards) that it's difficult, obscure, or at least exotic. For instance, when Le's The Boat came out and started piling up accolades, I remember reading an article that pointed to The Boat as an example of how all the good reviews in the world couldn't make a weird foreign book sell as much as Dan Brown.

Now, obviously very few authors regardless of nationality or critical acclaim sell as much as Dan Brown, so it's a pretty unfair comparison. But I still wonder if it would have occured to anyone to use this book, written in English by an Australian lawyer living in the US, as an example of weird foreign literature had the writer's name been Bill Johnson. Because honestly, if anything stays with me after reading it, it's how original it's not.

Which isn't to say that it's bad. It really is world literature in the literal sense, in that each of the seven stories in it is set in different parts of the world, and Le is obviously aware of the risk of being filed under "exotic foreigner" and deals with it right away in the first story, in which a Vietnamese-Australian writer named Nam Le is told by his friends to stop trying to write general fiction and just write about his Vietnamese father's horrible experiences during the war. Which, as it turns out, isn't a good idea at all. So from there he bounces us from the US to Colombia to Australia to Japan to Iran before finally returning to (or, to be exact, leaving) Vietnam, covering deceptively simple stories about people trying to take some small amount of control of their lives in a world where most things that happen to them are beyond their influence. And even if it's occasionally obvious that Le isn't quite fully developed as a writer yet (more than once, he seems to have started a story with a few overcooked phrases and then stretched the rest of the story to fit them in rather than killing his darlings) he has a great command of emotions and characters. At his best – say, the story about the American woman trying to understand the complexities of Iranian politics, or the Japanese girl in Hiroshima who unknowningly explains to us how indoctrination works – he's almost brilliant.

And yet, I'm left mostly shrugging. His stories have a tendency to fizzle out without really delivering all they could; he doesn't depend on twist endings, which is admirable, but instead he goes the other direction and too often fails to surprise us at all. Here's where I'm puzzled that anyone would think this is in any way difficult literature: it's all basically Babel or Crash, one of those "we're all the same underneath and everything's connected" movies Hollywood has been pumping out in recent years, with some hard questions that are ultimately simplified, dodged and answered only with emotional payoffs. As such, it gets the job done, even if it's mostly a job that's been done before. Does he deserve to be read more than Dan Brown? Well, who doesn't. Give him a few years and a proper plot to hang his writing on and he might deliver, because there's definitely stuff going on beneath the surface. As it is, though, The Boat neither rocks nor sinks.

Björn betygsatte Världens lyckligaste folk: 4 stjärnor

Björn betygsatte Mäktig tussilago: 3 stjärnor

Björn recenserade 1632 av Eric Flint

None

3 stjärnor

Sometimes, a writer will come up with a watertight plot. Sometimes... not so much.

Robert Ludlum wrote a foreword for The Road To Gandolfo where he said that he really hadn't intended for his novel (about a former US soldier kidnapping the pope and replacing him with a failed opera singer) to turn into a comedy. It was just that the more he worked at it, the more a voice at the back of his head kept screaming with laughter: "You can NOT be serious!" And so eventually, he couldn't make the plot work, and gave up and just let it be a self-parody.

Eric Flint doesn't do that, though it must have been tempting. He has a plot that hinges on something that makes no rational sense in the world he wants to set it, about a West Virginia coal-mining town from the year 2000 getting sent back to …

Sometimes, a writer will come up with a watertight plot. Sometimes... not so much.

Robert Ludlum wrote a foreword for The Road To Gandolfo where he said that he really hadn't intended for his novel (about a former US soldier kidnapping the pope and replacing him with a failed opera singer) to turn into a comedy. It was just that the more he worked at it, the more a voice at the back of his head kept screaming with laughter: "You can NOT be serious!" And so eventually, he couldn't make the plot work, and gave up and just let it be a self-parody.

Eric Flint doesn't do that, though it must have been tempting. He has a plot that hinges on something that makes no rational sense in the world he wants to set it, about a West Virginia coal-mining town from the year 2000 getting sent back to the 30 Years' War, and so he opens with an introduction that essentially says: "Aliens did it. I'm not going to mention them again. They have nothing to do with the plot at all. But just so you know - the reason a chunk of West Virginia is now in 17th century Germany? Aliens. Now, let's not worry about the hows and just get on with the story."

It really takes the pressure off, gives the readers a chance to decide for themselves how seriously they want to take the story while he gets to play it more or less straight. That's good. Because if I were to try to take this story completely seriously, I'd probably hate it. That's the problem with a writer like Dan Brown, for instance; he lays claim to credibility that he simply cannot live up to, while Flint starts it all off with a knowing wink.

Anyway, I'm sure you can guess what happens when a bunch of hard-workin' straight-shootin' no-bullshittin' mountain folk end up in the middle of a huge war over religion and politics; they cock their 21st century shotguns, load up the pickup, blast Reba McEntire and decide to start the American revolution a few hundred years earlier. And to do this, of course, they join up with the good protestant king Gustav Adolf of Sweden and start kicking papist ass. It's to Flint's credit, though, that for all its flirts with jingoism, machismo and blond-heroes-vs-swarthy-heathens, 1632 never becomes the flag-waving God&Guns fantasy it might have. Flint's WVians aren't necessarily PC liberals, but the novel constantly checks itself, asking what can be done, what should be done, arguing tolerance, adaptation and co-operation over domination and isolation. That's good too. And it's interesting to see the choices they have to make to try and survive and help out when there's just a handful of them caught up in one of the most devastating wars of all history; as one Vietnam war veteran puts it, all he knows how to do is call in air support, and they're not getting any of that. They have to build from scratch, and they can't do it alone.

What's not so good is... well, as entertaining as it often is, and it is a lot of fun watching him play out his over-the-top plot as if it made perfect sense, nobody could really call Flint a good writer. His prose is functional meat-n-potatoes stuff at best, unbearably flowery at worst, and his characters are for the most part painfully one-dimensional; the time travel trip that means they'll never get back home doesn't really impact the characters much, the good guys are completely good with no flaws or doubts whatsoever, the bad guys are bad baddy bad bad, and the poor people caught in between are just misled and have no problem at all adapting to the new way of things. Flint has certainly done his homework - perhaps a little too much so - on early-modern warfare and technology, but perhaps not so much on the other differences that have played out over the last 400 years.

But nevermind; aliens did it. 1632 is an entertaining romp, one with perhaps more thought put into it than it needed to be just an entertaining romp, and while some of it falls flat on its face (and please, Flint, get someone who speaks German to write the German dialogue for you) I can't help but admire the sheer ballsiness of it.

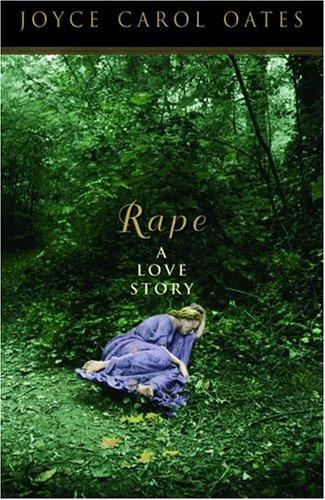

Björn betygsatte Rape: a love story: 4 stjärnor

Rape: a love story av Joyce Carol Oates

The victim of a Fourth of July gang rape, single mother Teena Maguire and her daughter become the target of …

Björn betygsatte The restless supermarket: 5 stjärnor

Björn recenserade Utrensning (in Russian)

Utrensning (in Russian)

None

5 stjärnor

World War II and the cold war gave birth to the modern spy thriller, where everything was about uncovering secrets and false loyalties. In Purge, Oksanen seems to bury it once and for all, while at the same time reminding her readers that there are always going to be those who remember where the bodies are buried. The wars are over here, democracy and freedom have won the day, the KGB archives are opened, the oppressed are getting back what they lost and all the old lies are going to be uncovered... well, the ones the winners want uncovered, that is. It's not going to be easy. There's going to be deaths, both new and old, before it's over.

It's early 90s in newly independent Estonia, where the old woman Aliide has lived alone in her little cottage for years. As an old Soviet functionary she's despised and feared by …

World War II and the cold war gave birth to the modern spy thriller, where everything was about uncovering secrets and false loyalties. In Purge, Oksanen seems to bury it once and for all, while at the same time reminding her readers that there are always going to be those who remember where the bodies are buried. The wars are over here, democracy and freedom have won the day, the KGB archives are opened, the oppressed are getting back what they lost and all the old lies are going to be uncovered... well, the ones the winners want uncovered, that is. It's not going to be easy. There's going to be deaths, both new and old, before it's over.

It's early 90s in newly independent Estonia, where the old woman Aliide has lived alone in her little cottage for years. As an old Soviet functionary she's despised and feared by her neighbours - a witch who may still have some sort of powers left. Children write insults on her door and throw rocks at her house, but nobody dares do anything more than that to drive her out. There's the big history, the collective one; 45 years of occupation and oppression can't not leave traces in a country that ceased to exist for decades and now has to be reinvented from the bits of history they can bear to remember.

Then one day, Aliide finds a young woman in her yard. Zara comes from Vladivostok and speaks the slightly archaic and accented Estonian of one born in exile. What she's doing in this part of the world is obvious from her outfit, make-up and skittishness; she's running from men in a big black car. That's the big history, the collective one: so many Balts were sent East by Stalin in the 40s and 50s, so many East European and Asian women are sent West nowadays to work in the thriving European sex trade.

Everything was repeating. Even though the ruble had been exchanged for the kroon, though there weren't as many fighter planes flying overhead, though the officer's wives had lowered their voices, though the anthem of independence blared from the speakers on Pikk Hermann every day, there was always a new leather boot, there was always a new boot, the same or different, always tramping in the same way across your throat.

But we know that, right? Dictatorship bad, democracy good, trafficking bad, etc. What makes Purge a great, entertaining, and uneasy bitches' brew of a novel is the way it interweaves the personal history with the big one, how they affect each other, and what exactly it is we build this bright new freedom on. How did these particular women end up on this particular farm of all places, what did they bring, and what's buried there? As Aliide and Zara sit there waiting for the big black car to inevitably find them Oksanen takes us back and forth through their history, tracing them from a young naive girl in the 30s through the shifting loyalties of the war, the Soviet years with its paranoia and secrets, on into the 90s. History is written by the victors, it's said, but of course losers write their history as well, why they were right, why their day will come, and what definitely didn't happen no matter what the other side may say. And in both Aliide's and Zara's life - and in the Soviet and Estonian records - there's so much that hasn't happened (can't have happened, mustn't have happened).

Purge is reminiscent of Ian McEwant's Atonement in some ways: a masterful character drama based on our ability - our need - to sometimes lie to ourselves, re-tell the story not just to justify our own actions but to make heroes of the people who may just have been victims. To be able to live with ourselves. But unlike McEwan, Oksanen dares to give the screw another turn, in both cold fury and compassion, and explore the darker sides of what the cultivation of victimhood can lead to, the righteousness, the elective blindness.

The title refers to deportation, to expulsion. To exorcism of old demons, to witch trials. To catharsis and self-delusion. To cleansing (and we know what meaning the 90s gave to that word). To execution. All of it will finally come to the surface in that little cottage on the edge of an Estonian forest, where the ground is still poisoned since Chernobyl (since 1946, since 1942, since 1917, since Adam and Eve) and Aliide has spent decades filling her dark cellar with preserved goods. When the big history and the small ones collide, something's going to explode. And then, once again, someone's going to have to clean up the blood, hide the bodies, and pick a winner.