Björn betygsatte The Ocean at the End of the Lane: 4 stjärnor

The Ocean at the End of the Lane av Neil Gaiman

A middle-aged man returns to his childhood home to attend a funeral. Although the house he lived in is long …

Den här länken öppnas i ett popup-fönster

A middle-aged man returns to his childhood home to attend a funeral. Although the house he lived in is long …

William Stoner is born at the end of the nineteenth century into a dirt-poor Missouri farming family. Sent to the …

Relegated to the status of schoolteacher and friendly neighbor after abandoning her dreams of becoming an artist, Nora advocates on …

It's 1989. Bohumil Hrabal is old. He writes letters to a young American named April, called Dubenka, a young woman fascinated with Bohemian (capital B) culture and his writing, which he thinks is mostly in the past.

He writes about aging, about the grief over his dead wife, about the kittens he takes care of.

He writes – extensively – about the concept of killing yourself by jumping out of a fifth floor window. (Defenestration, after all, is a genuinely Pragueish concept.)

He writes about hanging out at his old pub, drinking beer. Really, there's an awful lot of beer in this.

He writes about literature, art, movies. He fanboys Hasek, Sandburg, Warhol and Kerouac, he ponders Kundera and Havel – the ones who went in exile (whether abroad or in jail) for their convictions, while he refused to sign the charter and stayed to be able to write brilliant, …

It's 1989. Bohumil Hrabal is old. He writes letters to a young American named April, called Dubenka, a young woman fascinated with Bohemian (capital B) culture and his writing, which he thinks is mostly in the past.

He writes about aging, about the grief over his dead wife, about the kittens he takes care of.

He writes – extensively – about the concept of killing yourself by jumping out of a fifth floor window. (Defenestration, after all, is a genuinely Pragueish concept.)

He writes about hanging out at his old pub, drinking beer. Really, there's an awful lot of beer in this.

He writes about literature, art, movies. He fanboys Hasek, Sandburg, Warhol and Kerouac, he ponders Kundera and Havel – the ones who went in exile (whether abroad or in jail) for their convictions, while he refused to sign the charter and stayed to be able to write brilliant, subversive but not overtly political books.

He writes to a young American who seems to have opened a window for him, a new way of looking at himself and his work. He writes about his life, his youth, his books, how unashamedly (and rightly so) proud he is of Too Loud A Solitude and what he had to do to be able to write it.

He writes about the American book tour she set up for him, a Spinal Tap-esque trip through a strange land filled with strange people (being cluelessly if benignly racist in the process), speaking at colleges where they only want to ask him about politics, trying to get photo ops with people he admires who may or may not have ever heard of a drunken, aging Czech genius.

And how it all seems to go out the window (and yet somehow becomes even more important) when the demonstrations start in Vaclav Square, when the velvet revolution comes, when students take to the streets and demand the freedom he always found in writing. Does he have the right to join them? Does he have the duty? Does he even want to?

He writes letters. He doesn't send them. Seven years later, after he falls out of a fifth floor window while feeding pigeons – it's ruled an accident, of course – presumably, she gets to read them. And I can't help but wonder if she recognises herself.

Everytime god – or the government, which pretty much adds up to the same thing in the 20th century – closes a door, people open windows instead. Bohumil Hrabal's books is one of the most fascinating ones, and his autobiography (if you can call this spontaneous, funny, matter-of-factly sad, self-righteous, self-deprecating collection of letters that) is no exception. I can't do the beauty of his prose justice with anything I could write, but you owe it to yourself to read Hrabal.

"Autencitet är bara ett litterärt grepp." Det var Mircea Cartarescu som sade det, men jag tror Lindgren skulle hålla med, eller åtminstone nicka eftertänksamt medan han suger på pipan och hittar ett sätt att kvalificera det på en mening som är mer kärnfullt och mer mångtydigt än något jag kunde få ihop på en A4.

Klingsor är Lindgren på skrönehumör - tänk Dorés bibel så är ni inte miltals därifrån - nästan helt utan de där små stänken av magisk realism han tar till ibland, en enkel historia om en högst medelmåttig konstnär från Västerbotten som med god teknik målar exakt samma sak om och om och om igen utan att variera sig. Han målar döda ting för att hitta livet i dem, återger dem så som de är som om det vore sanning. Lindgren smyger runt bland begreppen - konst som livgivare, konst som mord, konst som begrepp - …

"Autencitet är bara ett litterärt grepp." Det var Mircea Cartarescu som sade det, men jag tror Lindgren skulle hålla med, eller åtminstone nicka eftertänksamt medan han suger på pipan och hittar ett sätt att kvalificera det på en mening som är mer kärnfullt och mer mångtydigt än något jag kunde få ihop på en A4.

Klingsor är Lindgren på skrönehumör - tänk Dorés bibel så är ni inte miltals därifrån - nästan helt utan de där små stänken av magisk realism han tar till ibland, en enkel historia om en högst medelmåttig konstnär från Västerbotten som med god teknik målar exakt samma sak om och om och om igen utan att variera sig. Han målar döda ting för att hitta livet i dem, återger dem så som de är som om det vore sanning. Lindgren smyger runt bland begreppen - konst som livgivare, konst som mord, konst som begrepp - medan Klingsor ljuger, mördar och allmänt bär sig åt som en psykopat (det förväntar man sig ju av stora konstnärer) och berättarrösten entusiastiskt kräver av läsaren att försöka leta upp några av hans konstverk, som ju nästan alla gått förlorade. (Det är lite av Vonneguts Bluebeard i detta, men också nästan inget.)

Lindgren kokar soppa på, inte en spik utan tvärtom på precis allting, och så kokar han den tills den blir klar och smaskig och går ner så fort att man knappt inser hur mättande och god den var förrän efteråt.

Yeah, dystopias are the new black and most of them are a hopelessly bland, unchallenging shadow of what they might need to be, Orwell Light designed to be filmed and passing off general "darkness" as a substitute for actual subversivness. And self-published to boot? Puh-leeeze.

So yes, I'm well prepared to hate this, but Howey wins me over pretty much immediately - the opening section (which was also the original novella, which he then expanded on) is a great start, tossing us right into a situation that carries with it a bunch of, if not hard, then at least intriguing questions. There's been some sort of major disaster, and what's left of mankind is locked in a huge bunker, told the outside lethal, and sentencing people to certain death outside if they question this... And killing them by making them go out and clean the cameras that show people just …

Yeah, dystopias are the new black and most of them are a hopelessly bland, unchallenging shadow of what they might need to be, Orwell Light designed to be filmed and passing off general "darkness" as a substitute for actual subversivness. And self-published to boot? Puh-leeeze.

So yes, I'm well prepared to hate this, but Howey wins me over pretty much immediately - the opening section (which was also the original novella, which he then expanded on) is a great start, tossing us right into a situation that carries with it a bunch of, if not hard, then at least intriguing questions. There's been some sort of major disaster, and what's left of mankind is locked in a huge bunker, told the outside lethal, and sentencing people to certain death outside if they question this... And killing them by making them go out and clean the cameras that show people just HOW uninhabitable the outside world is. It's a brilliant setup that lets Howey play around a lot with the various classes that have formed inside - basically setting up a postmodern Metropolis, with proles vs techheads and a population too comfortable and (rightly) afraid of rocking the boat to challenge the situation. Howey constructs a mostly very believable world, with characters shaped by centuries of fear and survival instinct - fear is easy to weaponise, especially if there really is something to fear and one panicked riot could easily kill off humanity.

So yeah, eventually it does become a bit obvious that 90% of the novel is tacked onto a short story, with a fair amount of padding and a shoehorned Romeo And Juliet plot that mostly seems to be there to provide a crutch. And of course, the end result is mostly about confirming what every other (American) story of the past few decades has already told us (along with some of the usual "information wants to be FREEEE!" bullshit). But Howey's a good enough writer to pull it off, and once he's established the main conflict he delivers one hell of an action ride that's, if not revolutionary, clever enough to make me walk around counting the moments until I have time to pick it up again and keep reading.

History repeats

Hysteria tropes

A theorist preys:

A prehistory set -

Rephrase it: toys

Reshape: riot, sty

Oh, spry treatise,

Pharisees to try?

Potty hearse, Sir!

Theatre is prosy,

Shit, reaper toys.

Thy sport easier.

Reraise thy post:

Rosiest therapy

Er, eat sophistry

Share posterity

Repeat his story

History repeats

And we learn nothing

But the beauty

And decay from which it grows anew.

Dualities?

All audits lie.

Literature is incest.

Elasticities return.

/I, rearrangement servant.

You know the sort of plot where there's something the narrator isn't telling us, because if he told us too soon there'd be no plot, but he can't actually come up with a very good reason not to tell us?

Unseen Academicals is fairly mediocre, as Discworld novels go. There's magic in it (though some of the best bits come after magic is literally removed from it), there are cameos by all your favourite characters (though they come across more as checking boxes), there are some very nice (but rather preachy) sentiments about tolerance and intolerance, mob mentality, and the like. And when it's good, it's often quite good; fans of Vetinari and Ridcully, especially, should have a lot of fun. But it's also a fairly unfocused novel, padded with half-mumbled character exposition, using Romeo & Juliet and various lads' football comics as crutches to keep the story doing anything …

You know the sort of plot where there's something the narrator isn't telling us, because if he told us too soon there'd be no plot, but he can't actually come up with a very good reason not to tell us?

Unseen Academicals is fairly mediocre, as Discworld novels go. There's magic in it (though some of the best bits come after magic is literally removed from it), there are cameos by all your favourite characters (though they come across more as checking boxes), there are some very nice (but rather preachy) sentiments about tolerance and intolerance, mob mentality, and the like. And when it's good, it's often quite good; fans of Vetinari and Ridcully, especially, should have a lot of fun. But it's also a fairly unfocused novel, padded with half-mumbled character exposition, using Romeo & Juliet and various lads' football comics as crutches to keep the story doing anything until Pratchett gets to where he really wants to go. When he does get there, it's all very serviceable, and for any other author it would be a solid novel; but I expect more of Pratchett.

On the one hand, a fantastic document; Black Hawk's autobiography (in reality, more an extended interview) from the stories of his grandfather who met the first French colonists in Canada, to his decision to make a stand against the United States after having one too many deals disregarded and his people gunned down under parliamentary flag, to his defeat. As a first-hand account, it's invaluable, and paints a much-needed counternarrative to the traditional view - which, yeah, has become much more commonplace over the last 50 years or so, but this was written and published THEN, making it even clearer that the contemporary view of Native Americans as "savages" was little more than wishful thinking; all the evidence to the contrary was easily available if they wanted it. Black Hawk's analysis of the colonial attitude is, occasionally, still frighteningly applicable.

Bad and cruel as our people were treated by the …

On the one hand, a fantastic document; Black Hawk's autobiography (in reality, more an extended interview) from the stories of his grandfather who met the first French colonists in Canada, to his decision to make a stand against the United States after having one too many deals disregarded and his people gunned down under parliamentary flag, to his defeat. As a first-hand account, it's invaluable, and paints a much-needed counternarrative to the traditional view - which, yeah, has become much more commonplace over the last 50 years or so, but this was written and published THEN, making it even clearer that the contemporary view of Native Americans as "savages" was little more than wishful thinking; all the evidence to the contrary was easily available if they wanted it. Black Hawk's analysis of the colonial attitude is, occasionally, still frighteningly applicable.

Bad and cruel as our people were treated by the whites, not one of them was hurt or molested by our band. (...) The whites [who were settling on his land] were complaining at the same time that we were intruding upon their rights. They made it appear that they were the injured party, and we the intruders. They called loudly to the great war chief to protect their property.

How smooth must be the language of the whites, when they can make right look like wrong, and wrong like right.

On the other hand, Black Hawk lost more than just land, people, and a war. While his translator and biographer no doubt were sympathetic to him and did their job as fairly as was possible, there's still the feeling that not only do they still play up stereotypes (positive ones rather than negative, but still) and as one commenter has said, use the noble defeated warrior to make white people feel good about themselves. But above all they rob him of his language. After he's filtered through two well-meaning 19th century gentlemen writing for their audience, he comes out speaking like a Dickens character. Couple this with the decision to present his story as one long monologue, unedited and without contextualisation, and this rare authentic story looks curiously inauthentic and inaccessible to a modern reader. I find myself wanting to go back in time and hand the translator a tape recorder, so it'll be possible for someone in a future where people actually want to read Black Hawk's own words to retranslate the book.

The Gutenberg edition helps this somewhat by not only containing Black Hawk's own story but also a number of appendices about the Black Hawk War. It also adds some unfortunate proofreading errors, though, such as the US ordering Black Hawk to "buy the hatchet", which, um...

Helt underbart nördig, intelligent, rolig och lagom bitskt subversiv redogörelse för hur grammatik fungerar. Eller om man så vill, hur vi berättar vad vi gör - med, mot, av, för, i, eller bara lite intransitivt i allmänhet sådär, världen och varandra. Skarpt och lekfullt som en Tage Danielsson filtrerad genom queerteori. Den som kan reglerna kan skriva nya.

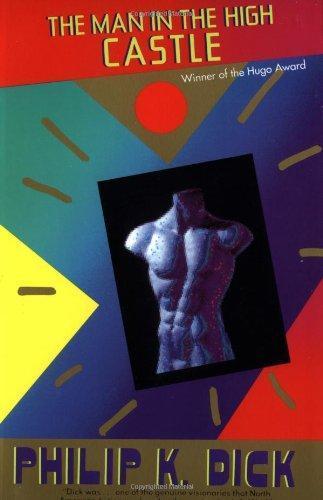

The Man in the High Castle is an alternate history novel by American writer Philip K. Dick. Published and set …

Mother Night is a novel by American author Kurt Vonnegut, first published in February 1962. The title of the book …