Det är slående hur Harrison genomgående kan skriva ordet "homosexuell" så att man hör att han uttalar det med långa O.

Mannen från Barnsdale är en väldigt lärd genomgång av myten runt Robin Hood, dess rötter, dess historia och de olika skepnader den tagit genom århundradena. Oavsett om man kommer fram till samma slutsatser som han (att det faktiskt fanns en Robert Hode, en John Lytell, och en väldigt ökänd Sheriff i Yorkshire på 1320-talet som med lite god vilja passar väldigt väl in...) så är det fan så mycket mer intressant att leta efter rötterna till en myt än att bara säga "Det var påhittat alltihop, punkt slut. Fast just därför känns hans föraktfulla avfärdande av alla idéer om att mytologi skulle ha någon som helst betydelse för medeltida litteratur, och hans ständiga hojtande om "politisk korrekthet!!1!" runt senare filmer (som om inte alla filmer varit produkter av sin …

Granskningar och kommentarer

Den här länken öppnas i ett popup-fönster

Björn recenserade Mannen från Barnsdale av Dick Harrison

None

3 stjärnor

Det är slående hur Harrison genomgående kan skriva ordet "homosexuell" så att man hör att han uttalar det med långa O.

Mannen från Barnsdale är en väldigt lärd genomgång av myten runt Robin Hood, dess rötter, dess historia och de olika skepnader den tagit genom århundradena. Oavsett om man kommer fram till samma slutsatser som han (att det faktiskt fanns en Robert Hode, en John Lytell, och en väldigt ökänd Sheriff i Yorkshire på 1320-talet som med lite god vilja passar väldigt väl in...) så är det fan så mycket mer intressant att leta efter rötterna till en myt än att bara säga "Det var påhittat alltihop, punkt slut. Fast just därför känns hans föraktfulla avfärdande av alla idéer om att mytologi skulle ha någon som helst betydelse för medeltida litteratur, och hans ständiga hojtande om "politisk korrekthet!!1!" runt senare filmer (som om inte alla filmer varit produkter av sin tid) lite fantasilöst, och det finns väl goda skäl till att han aldrig tjänat mycket pengar som filmkritiker.

Björn recenserade Men and cartoons av Jonathan Lethem

None

3 stjärnor

Lethem's second short story collection isn't a bad effort at all, but funnily enough (considering how good an essayist he is), I'm not sure the format suits him. Several of the pieces here feel like outtakes from a longer story, that sacrifice the character and thematic developments of a novel but don't quite pack the punch of a great short story. If you've read Fortress of Solitude (and you should) there's really not much new in stories like The Vision or Planet Big Zero, and sci-fi stories like Access Fantasy may be entertaining but come across as too obviously Vonnegut-meets-Bradbury without the sharp observations of either. That said, The Spray is a brilliant idea done very well (a couple are robbed, the police use a mystical spray to identify what's missing from their apartment, and the couple then turn the spray on each other to see what's unspoken between them...), …

Lethem's second short story collection isn't a bad effort at all, but funnily enough (considering how good an essayist he is), I'm not sure the format suits him. Several of the pieces here feel like outtakes from a longer story, that sacrifice the character and thematic developments of a novel but don't quite pack the punch of a great short story. If you've read Fortress of Solitude (and you should) there's really not much new in stories like The Vision or Planet Big Zero, and sci-fi stories like Access Fantasy may be entertaining but come across as too obviously Vonnegut-meets-Bradbury without the sharp observations of either. That said, The Spray is a brilliant idea done very well (a couple are robbed, the police use a mystical spray to identify what's missing from their apartment, and the couple then turn the spray on each other to see what's unspoken between them...), The Dystopianist, Thinking of his Rival, is Interrupted by a Knock on the Door is not just a great title, and Super Goat Man makes the perhaps best use yet of Lethem's fascination with comic book heroes by featuring a jaded and retired superhero trying to make a living as a college teacher in Nixon's America - and then showing us exactly why heroes retire, and what happens to those who trusted in them; superhero deconstructions are a thirteen per dozen these days, but Super Goat Man is one of the better.

Lethem is never not entertaining, and when he gets it right, that Pynchon-lite walk through an America built as much by Stan Lee as by Abraham Lincoln, populated by people trying to pick up the world their forebears handed them in bright colours promising caped baddies and upstanding heroes that somehow never delivered, works very well in short story form as well. But Men And Cartoons is a little too slight, with one or two stories too many that just fizzle out without going neither SPLAT nor POW.

Björn betygsatte SCHOOL OF WAR; TRANS. BY LAURIE WILSON.: 4 stjärnor

SCHOOL OF WAR; TRANS. BY LAURIE WILSON. av Alexandre Najjar

"Alexandre was eight years old when bloody and brutal hostilities erupted in Lebanon; he was twenty-three when the guns at …

Invisible av Paul Auster

Invisible is a novel by Paul Auster published in 2009 by Henry Holt and Company. The book is divided into …

Björn betygsatte Un roman russe: 2 stjärnor

Björn betygsatte Jag förbannar tidens flod: 4 stjärnor

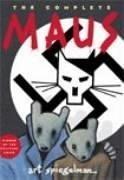

Björn betygsatte The Complete Maus: 5 stjärnor

The Complete Maus av Art Spiegelman

On the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of its first publication, here is the definitive edition of the book acclaimed …

Björn recenserade The hunger angel av Herta Müller

None

5 stjärnor

"A cattle-train wagon blues, a kilometre song of time set in motion."

It's an interesting choice of words Müller has her protagonist make to describe the long train ride at the end of World War II, packed in like sardines, the long cold way to the camp in the East. After all, the blues arose from a culture where the people had been deliberately robbed of their own languages and had them replaced with a rudimentary one, with the idea that they wouldn't be able to say - and by extension think - much besides "Yes sir, whatever you say" and "Praise God." The blues, on its surface, is a simple, repetitive language that always follows the same pattern, the same 12 bars to describe the trauma that makes up your life: I woke up this morning, all I had was gone, I woke up this morning, all I had …

"A cattle-train wagon blues, a kilometre song of time set in motion."

It's an interesting choice of words Müller has her protagonist make to describe the long train ride at the end of World War II, packed in like sardines, the long cold way to the camp in the East. After all, the blues arose from a culture where the people had been deliberately robbed of their own languages and had them replaced with a rudimentary one, with the idea that they wouldn't be able to say - and by extension think - much besides "Yes sir, whatever you say" and "Praise God." The blues, on its surface, is a simple, repetitive language that always follows the same pattern, the same 12 bars to describe the trauma that makes up your life: I woke up this morning, all I had was gone, I woke up this morning, all I had was gone, any day now I shall be released.

Of course, the characters of Atemschaukel (the English title will supposedly be the somewhat awkward Everything I Possess I Carry With Me) aren't slaves, at least not officially, and the camp they're off to isn't one of those camps. This is a few months later, January 1945, and the ones in the cars aren't Jews and Roma but Germans - well, sort of, it's a matter of language. As the Red Army conquered/liberated eastern Europe, one of their orders was that since the Germans were responsible for the destruction of their country, the Germans were expected to pay for its reconstruction. And hey, eastern Europe was full of ethnic Germans since the middle ages. Leo is 17, Romanian, homosexual, and German. As such, he's one of many who are given a couple of hours to pack what they need before they're shipped off to 5 years of hard labour deep in the Soviet Union.

Everything I possess I carry with me.

Or: Everything I own I carry on me.

I carried everything that I had. It wasn't mine. It was either intended for another purpose or belonged to someone else.

Atemschaukel ("breath swing" - the thing in your throat that may pass back and forth but can never be spat out or swallowed, chokes you up and keeps you alive, constantly on the threshold) is, on its surface, a harrowing Solzhenitsyan tale of everyday life in a forced labour camp; the cold, the hunger, the work, the guards, the inspections, the paranoia, the lice, the false cameraderie, the mistrust, the despair, the homesickness... and as such, it's a very strong work. But there's more to it.

It's a matter of language. Everyone but the guards and the people in the surrounding villages (where are they going to run to?) still speaks German, but in this new context the words have become poisoned, they lose their old meaning, all abstract ideas eventually starve and die. Leo can't read the books he brought along; he rips them up and sells Goethe and Nietzsche as cigarette or toilet paper. The commandant is called "Comrade". Love and marriage go together like a horse and a whip, one way of getting a little more to eat. Homesickness is hollowed out bit by bit until it means being sick for the place where you had food, but you don't get food unless you work, and so eventually "home" becomes the bowl and the shovel. And once language stops being reliable, stops working, there's nothing to hold everything together. Leo is set to carry cement, but the paper sacks are too heavy and too thin, and no matter how he tries the paper rips and the cement runs out into the mud or blows away on the wind or sticks to his skin and seals him up.

Without a language, without a binding element, you won't survive. You'll freeze, you'll starve, you'll have an accident and drown in concrete. So he has to create a new language to describe the new world - auf Deutsch, of course, the German language is famous for its ability to make new words simply by sticking two old ones together; grammar makes no moral judgement. Year by year, he transforms himself into someone who can survive, with a new world of ideas, and new words.

Hunger angel: The closest to a god or an ideal here, always hovers over you, controls your every thought, keeps you alive, stops you living.

Own bread: What's left of the bread you had for breakfast at the end of the day. Always smaller than the others'.

Bread court: The spontaneous court that judges and punishes whoever eats what belongs to someone else.

Heart shovel: Your dance partner, hundreds of shovels per day, until your entire biorhythm is controlled by work and hunger.

The great thing about novels is their ability to create or recreate something, whether factually true or false, and make the reader see the truth in it. In Atemschaukel, Müller does exactly that, with a lot of help from poet Oskar Pastior who (like Müller's mother) was in one of the camps and is the "real" Leo. But it does more than that. It's not just about a Soviet labour camp. For all the routine in its day-to-day chores, it's a tremendously inventive, sneaky and deathly serious piece of metafiction (meta reality?) where it's a matter of language. How the world forms the way we see the world, attaches certain meanings to certain words, and how it can fundamentally change us. "I know you'll come back", Leo's grandmother tells him before he leaves, and those words become a mantra that keeps him alive. But who's the man who comes back? They didn't even know who he was when he left, he would have been tossed in jail for who he was, or ended up in a different kind of camp. The man who comes back has had his entire concept of the world changed, his words no longer mean what their words mean. But he's free now, right? Bread just means bread again, a spade is just a spade.

The camp let me leave only to create the distance needed for it to take up more space in my head. Since I came home, my keepsakes don't say HERE I AM anymore, but they don't say I WAS THERE either. My keepsakes say: I'LL NEVER GET OUT OF THERE.

150 years ago, slavery was abolished. 65 years ago, fascism died. 20 years ago, the Wall came down. Democracy means democracy again. Freedom means freedom again. Fascism means fascism again. Worker means worker again. Hunger just means hunger again. Why are you still using those words to mean what they meant to you for a generation or ten? Here, look at the dictionary: bread is just flour, water and yeast, that's all. Get your act together. You're free now.

Blow yer harmonica, son.

Björn recenserade The world without us av Alan Weisman

'Maailma ilman meitä on ajatusleikki siitä, mitä maailmalle tapahtuisi, jos ihmiskunta häviäisi. Mitä tapahtuisi seuraavana …

None

3 stjärnor

After a decade or two, nature - first plants, then wild animals - will have taken over our cities. Much to the horror of those species that depend on us for their survival, both those we've domesticated and those we consider vermin. New York City will finally be free of cockroaches, that's something, right?

After a hundred years or two, our modern concrete-and-cardboard houses will have started falling apart (if they haven't already burned down or been flooded or knocked over by earthquakes.) Our domesticated animals and plants will for the most part be extinct, replaced by species that know how to survive in the wild; horses and cats will probably make it, cows and pigs may survive on isolated islands where we've gotten rid of predators and natural competition (Hawaii, Great Britain). Some of our most celebrated feats of engineering - the Panama canal, the skyscrapers, the subway systems …

After a decade or two, nature - first plants, then wild animals - will have taken over our cities. Much to the horror of those species that depend on us for their survival, both those we've domesticated and those we consider vermin. New York City will finally be free of cockroaches, that's something, right?

After a hundred years or two, our modern concrete-and-cardboard houses will have started falling apart (if they haven't already burned down or been flooded or knocked over by earthquakes.) Our domesticated animals and plants will for the most part be extinct, replaced by species that know how to survive in the wild; horses and cats will probably make it, cows and pigs may survive on isolated islands where we've gotten rid of predators and natural competition (Hawaii, Great Britain). Some of our most celebrated feats of engineering - the Panama canal, the skyscrapers, the subway systems - will probably be destroyed.

After a few thousand years, most of our artefacts will be as invisible as the Mayan cities were before they were rediscovered a few decades ago. Some of our more well-constructed buildings and artworks - the pyramids, the great cathedrals and temples, Mount Rushmore, the Channel Tunnel, every bronze statue ever made - may still be around, even if they've started falling apart with no one to maintain them. The forests will have slowly started to spread across the world again.

After a few hundred thousand years, microbes may have evolved to eat the plastic we've left behind. CO2 levels will probably have returned to pre-1800s levels. Much of the radiation from the 400 nuclear reactors that went Chernobyl with nobody to maintain them will have dissipated. There will still be traces of the human race - both in ancient caves and ruins and in the form of chromed, stainless-steel cookware - which in a million years or two may or may not puzzle some other species which may or may not slowly start to take our place.

If we were to disappear today.

That's the basic premise that makes up The World Without Us; the human race vanishes - either instantly (raptured by a deity, kidnapped by aliens) or within a generation or two (a virus, a voluntary extinction movement). The how and why isn't really important for the thought experiment; just assume that all ~7 billion of us were suddenly gone without destroying everything else in the process. What would happen to the rest of the world?

In order to answer the question Weisman has put together an impressive picture with the help of experts from multiple disciplines, looking at our history and our present to predict a future that doesn't have us in it. Naturally, his purpose isn't to wish for the death of the human race, but to put a perspective on how we live today. And for the most part, it's a fascinating read even if he's a little too fond of details at times and there's a couple of points which are based on slightly dodgy assumptions. Up until the preachy ending he rarely takes a moral stance, just describes the impact - for better or worse - that the human race has had on the planet since we first discovered fire, and will continue to have for some time to come, along with well-founded speculations of what might happen if we suddenly left it alone. The world would do fine without us, he concludes - illustrating it most poignantly with visits to some of the very few areas in the world which humans have left alone for a few decades (ironically, usually due to war - the DMZs in Korea and Cyprus, for instance) and have quickly been reclaimed by nature. It's survived a lot worse, after all. But as long as we're its guests, we should at least be aware of when we're tracking mud over the floor.

Wu Ming: 54 (2006, Penguin Random House)

None

4 stjärnor

Spring, 1954. Stalin is dead, the cold war is starting to take the shape it would hold for a generation to come, Joe McCarthy is kicking commie ass and taking names, the French are in trouble in Indochina, and in the free territory of Trieste between Italy and Slovenia the big boys are trying to wrap up the last of the unresolved border disputes following WWII. Of course, to do this, it helps if they have Tito on their side. And so the MI6 call in Tito's favourite movie star to convince him... yes, it's Cary Grant, secret agent. Meanwhile, Lucky Luciano and his gang are setting up the world's heroin trade, a young Triestean is searching for his father who disappeared into Yugoslavia during the partisan years, a poor American TV set gets stolen and keeps changing owners, and a bunch of old Italians sit around at their local …

Spring, 1954. Stalin is dead, the cold war is starting to take the shape it would hold for a generation to come, Joe McCarthy is kicking commie ass and taking names, the French are in trouble in Indochina, and in the free territory of Trieste between Italy and Slovenia the big boys are trying to wrap up the last of the unresolved border disputes following WWII. Of course, to do this, it helps if they have Tito on their side. And so the MI6 call in Tito's favourite movie star to convince him... yes, it's Cary Grant, secret agent. Meanwhile, Lucky Luciano and his gang are setting up the world's heroin trade, a young Triestean is searching for his father who disappeared into Yugoslavia during the partisan years, a poor American TV set gets stolen and keeps changing owners, and a bunch of old Italians sit around at their local bar solving the world's problems over an espresso.

If this all sounds both confusing and insane, that's because it is... sorry, I meant to say, that's because it is the plot of a very ambitious 550-page novel condensed into a few sentences. Wu Ming, AKA Luther Blissett, the collective pseudonym of no less than five Italian writers, have managed something quite impressive here: it's a novel that almost manages to balance a... I mean several political thriller plots with a wild sense of humour, an underlying metaphor of the beginning US domination of the Western world both in terms of military and culture (if slightly hamfisted - there's an American TV set full of heroin, ferchrissakes, talk about your Trojan horse), a lament for/satire of the failure of democratic socialism in the post-fascist age, an attempt to sketch the outlines of a "post-war" half-century which would start with 20 years of war in Vietnam and end in Iraq and Afghanistan, plus a just all-around entertaining riff on spy and war novels. Basically, they're trying to write V, The Odyssey, Casino Royale, Underworld, Pereira Declares and The Godfather all at once. And have fun with all of them.

And the thing is, they almost manage to keep it together, anchor it just enough in reality and history to make even the more madcap parts believable. Obviously, it sprawls. With five writers working together, you have five people wanting their favourite bits in, so it gets overwritten; and with a bunch of storylines stretching out from Mexico to Dien Bien Phu and from Hollywood to Dubrovnik, with literally dozens of protagonists, they end up working just a little too hard to tie them all together. But damnit, it's flawed, but it works. For one thing, because they keep coming back to their characters and building the plot from them rather than the other way around. Even Cary Grant isn't in it as the movie star, he's in it as the struggling 50-year-old soon-to-be-has-been who's never reconciled himself with the working-class lad Archie Leach who wanted to be an actor, a living embodiment of both class, cultural and personal conflicts. You laugh at them, yes, but you smile with them and wince for them too. For another, it's so much fun that like political or philosophical ideals, it just makes you want to believe in it even when you know it's not practically feasible. In the end, of course, nothing here changes history in any big way (the last scene notwithstanding). Most of the time, individuals - even dozens of individuals working in separate storylines - don't change the world at large. Some of them die, some of them run away, some just stay at home and do their job, and the world marches on towards what we have today. But damnit, it's entertaining. It captures a world on the cusp of something, that wants to go in several different directions, but for reasons that become painfully clear end up going in a direction very few of them actually want to go. Takes out the warmth, leaves in the fire.

Björn recenserade The Man Who Was Thursday av G. K. Chesterton (The Modern Library classics)

None

3 stjärnor

I wasn't all that impressed with the book, though I didn't really dislike it either. I started reading with absolutely no idea of what the book was about (Gutenberg.org editions don't really have blurbs on the back cover). At first I thought it was a sendup of revolutionary thought similar to Dostoyevsky's Demons, then I thought it was a sendup of revolutionary acts similar to Bulgakov's The Master And Margarita, then it descended into proto-James Bond, and by the end I wasn't sure what the hell it was.

At its heart, I guess it's more of a philosophical thriller than a political one - the hunt for an anarchist parading as the hunt for meaning, ref Nietzsche's infamous talk of killing God etc - and there are definitely some interesting discussions, even if all the characters seem so foolish that I'm not sure whether we're supposed to take anything they …

I wasn't all that impressed with the book, though I didn't really dislike it either. I started reading with absolutely no idea of what the book was about (Gutenberg.org editions don't really have blurbs on the back cover). At first I thought it was a sendup of revolutionary thought similar to Dostoyevsky's Demons, then I thought it was a sendup of revolutionary acts similar to Bulgakov's The Master And Margarita, then it descended into proto-James Bond, and by the end I wasn't sure what the hell it was.

At its heart, I guess it's more of a philosophical thriller than a political one - the hunt for an anarchist parading as the hunt for meaning, ref Nietzsche's infamous talk of killing God etc - and there are definitely some interesting discussions, even if all the characters seem so foolish that I'm not sure whether we're supposed to take anything they say seriously. Not to mention whether Chesterton even bothered understanding the reasons behind socialism or anarchism (probably not since they're more nihilists than anarchists); at least Dostoevsky seemed to admit they had legitimate complaints even as he skewered them. Then again, Chesterton's novel obviously isn't meant to be a realistic image of turn-of-the-century politics, so that didn't bother me too much.

It is very funny at times. The duel scene, the chase through London, the first few reveals of the Council members (before we realise where it's all headed), etc - Chesterton's language is (for the most part) a joy to read, his dialogue snaps and his characters do what they can in the midst of all the craziness.

"The work of the philosophical policeman," replied the man in blue, "is at once bolder and more subtle than that of the ordinary detective. The ordinary detective goes to pot-houses to arrest thieves; we go to artistic tea-parties to detect pessimists. The ordinary detective discovers from a ledger or a diary that a crime has been committed. We discover from a book of sonnets that a crime will be committed...We were only just in time to prevent the assassination at Hartlepool, and that was entirely due to the fact that our Mr. Wilks (a smart young fellow) thoroughly understood a triolet."

Who are the brain police, eh? The plot, however, I found predictable and the reveal at the end overly preachy. "HA! Silly humans, you cannot fathom the nature of God!" OK, if that's your thing, sure. But then, doesn't that essentially say that they were naive to ever try? The moral seems to be "Sit back, don't worry your pretty little heads about it, and trust that it'll all work out." Which bugs me a bit; whether in politics or philosophy, I'm not sure Chesterton understood the arguments he seems to try to refute.

As a farce, it's a lot of fun. As a thriller, it's nicely paced but predictable. As a philosophical work, it's flawed. But it made me laugh, both with it and at it.

Björn recenserade The Sorrows of an American av Siri Hustvedt

None

4 stjärnor

Now the ravens nest in the rotted roof of Chenoweth's old place

And no one's asking Cal about that scar upon his face

'Cause there's nothin' strange about an axe with bloodstains in the barn,

There's always some killin' you got to do around the farm

Murder in the red barn

Murder in the red barn

- Tom Waits

That song keeps playing in my head throughout The Sorrows Of An American - even though it's long unclear whether there's a murder in it at all. Apart from that one September, 2001 mass-murder that turns up as a (mostly, though not completely, unspoken) background for every mid-2000s New York novel, that is. There's a barn, though.

There's death, though. Three of them, to be precise... OK, a few more, but three that start the various plot lines of the story. Our narrator, Erik, has just buried his father (natural causes, …

Now the ravens nest in the rotted roof of Chenoweth's old place

And no one's asking Cal about that scar upon his face

'Cause there's nothin' strange about an axe with bloodstains in the barn,

There's always some killin' you got to do around the farm

Murder in the red barn

Murder in the red barn

- Tom Waits

That song keeps playing in my head throughout The Sorrows Of An American - even though it's long unclear whether there's a murder in it at all. Apart from that one September, 2001 mass-murder that turns up as a (mostly, though not completely, unspoken) background for every mid-2000s New York novel, that is. There's a barn, though.

There's death, though. Three of them, to be precise... OK, a few more, but three that start the various plot lines of the story. Our narrator, Erik, has just buried his father (natural causes, old age). While he and his recently widowed (natural causes, cancer) sister clean out their father's papers, they find a note:

June 27, 1937

Dear Lars,

I know you will never ever say nothing about what happened. We swore it on the BIBLE. It can't matter now she's in heaven or to those here on earth. I believe in your promise.

Lisa.

So there's secrets too. Was his father involved in a murder? (Well, OK, as a WWII vet he'd have been involved in quite a few deaths, but those aren't murders, are they?) What are the things we don't tell anyone, and nobody wants to ask about, while we're alive (especially if we, like Erik's family, are of hard-working grimly quiet Scandinavian stock and there are Things We Don't Talk About), but which people think they need to know about us after we're gone?

Tied into this is the sister's dead husband, a famous writer (not entirely dissimilar to a certain black-wearing postmodern author close to Hustvedt) whose life and wife is now fair game for the journalists; the mysterious beautiful single mother who just rented the flat below Erik and may be stalked by her ex; and Erik's own issues - including potential violent tendencies - which he is all too aware of.

I remember reading Hustvedt's previous novel, What I Loved, and coming away from it raving that not only was Paul Auster not the greatest novelist in the US, he wasn't even the greatest novelist in his own flat. I rated it a very solid . A couple of years later I can't really remember what specifically about it made me say that, which may be more my fault than Hustvedt's. But much like What I Loved, The Sorrows is basically everything you'd expect of a good (post)modern New York novel; middle-class white people in a suitably upgraded Brooklyn neighbourhood with artists lurking around every corner, dealing with their internal and external problems against a backstory leading back to the Old Country (in this case only a couple of generations, as evidenced by the family members occasionally slipping in the odd Norwegian word) and tackling the Big Questions of life and death and love and sex along the way. Franzen, Foer, all that lot.

Which is bit unfair against The Sorrows (and against Franzen and Foer) as it's really a rather good novel; it's just not a very surprising one. Along the way Hustvedt deals subtly, if somewhat conveniently at times, with the way life messes us up (as a psychoanalyst, Erik keeps coming back to the word "trauma"), the way we try to know each other and ourselves, the way honesty may be the most deceptive thing of all; does knowing The Truth about someone actually tell you the truth of who they are?

I miss the patients. It's hard to describe, but when people are in desperate need, something falls away. The posing that's part of the ordinary world vanishes, that How-are-you?-I'm-fine falseness. The patients might be raving or mute or even violent, but there's an existential urgency to them that's invigorating.

But still, seeing someone sick gives you one picture of who that person is. The book's villain, or as close as it comes to having a villain, runs around with a camera capturing supposedly authentic pictures of people; pictures don't lie (or well, he knows Photoshop) but the shutter speed is only a fraction of a second, yet that one picture overrules all the other fractions of a second that makes up a life. For deeper understanding of others and ourselves, we have stories; the narrative that shows us progression, facets, development, even if each chapter in the story is not the complete truth.

Trauma isn't part of a story; it is outside story. It is what we refuse to make part of our story.

Stories like, I suppose, this one. The Sorrows Of An American is a fine piece of fiction and it's very hard to find fault with it - OK, maybe the ending leaves a bit to be desired. But Hustvedt manages to make what could have been a very depressing novel into something life-affirming and even bleakly funny, with well-done characters and an excellent ear for dialogue. If you have to make the comparison (which isn't as unfair as it may seem, as they really do have a lot in common) I suppose one could argue that she and her husband mirror each other; he starts with the ideas and builds his stories on them, she starts with the story and digs until she finds the ideas - and unlike Auster's latest novels, her characters and their stories feel more genuine and less like author avatars. She hides her work, and she hides it behind a simple but effective prose that, like a good Scandinavian American should, says things without necessarily spelling them out.

It's not essential, it won't save or change your life, and if your taste is anything like mine you've probably read similar stories before. But who says every new novel has to reinvent the genre? Stories need to be told in order to exist, and this one deserves to live.