Having read Q&A after seeing Slumdog Millionaire, I'm convinced that one could cobble together one great story out of the two of them.

I liked the movie a lot when I saw it, but it's one of those where, the more I think about it, the more I'm unsure why exactly I liked it. Yes, Danny Boyle is a great director, the movie looks amazing and it's almost impossible to not be swept up in it, but I can definitely see why people are accusing him of "slum tourism"; the way he romanticizes the story, making everything fit nicely into a timeline of impossible coincidences and ending on that ridiculously sentimental ending where the poor boy wins it all and all the bad guys get what they deserve almost makes me wonder if he's being serious or if the point is to overdo it completely to point out just how …

Granskningar och kommentarer

Den här länken öppnas i ett popup-fönster

Björn recenserade Q & A av Vikas Swarup

None

2 stjärnor

Having read Q&A after seeing Slumdog Millionaire, I'm convinced that one could cobble together one great story out of the two of them.

I liked the movie a lot when I saw it, but it's one of those where, the more I think about it, the more I'm unsure why exactly I liked it. Yes, Danny Boyle is a great director, the movie looks amazing and it's almost impossible to not be swept up in it, but I can definitely see why people are accusing him of "slum tourism"; the way he romanticizes the story, making everything fit nicely into a timeline of impossible coincidences and ending on that ridiculously sentimental ending where the poor boy wins it all and all the bad guys get what they deserve almost makes me wonder if he's being serious or if the point is to overdo it completely to point out just how impossible it really is for a poor Indian orphan to become a success in New India.

Q&A, on the other hand, gets a lot of things right. I had heard that the plot was different, but I was surprised at how different. The entire backstory is changed, the individual episodes that lead up to him knowing the answers are often very different, changing the tone of the story quite a lot - not to mention that the protagonist is completely different. Not only his name, but the way he acts, the way he actually does things rather than sit back and wait for things to happen to him. I like that. And while Swarup isn't as great a writer as Boyle is a director, he gets the job done for the most part, even though the movie ends up a lot more coherent - yes, the book has a more believable story, but the movie's story is has a better narrative. Not unlike Hamid's The Reluctant Fundamentalist I never quite buy the illusion that the book is mostly one long monologue - especially since he makes a point of his narrator being so very uneducated - and it's mostly fairly superficial stuff, but hey, it zips nicely along and it goes into places the movie didn't. Where the movie is a story of one Indian boy's path to riches, the book does a better job of being about India itself - as suggested by our plucky hero having three names: one Muslim, one Christian, and one Hindu.

But then Swarup blows it all on the ending. I'm going to avoid spoilers, but it's definitely the biggest difference between the two versions; while both endings seem like almost impossible coincidences, at least Boyle's ending is the sort of ending you want to believe in even if you know it's probably impossible. Swarup's is just... poor. A couple of huge clichés on top of what was looking like a solid, if not great, novel that drags it down and makes me wish I'd skipped the last 15 pages.

Björn recenserade Man in the Dark av Paul Auster

None

3 stjärnor

A recently widowed writer, whose name by pure chance sounds a lot like "Paul Auster", lies on his back in a dark room. A car accident has temporarily disabled him, and so now he spends his nights sleepless on his daughter's couch in Vermont, telling himself stories to pass the time. Upstairs, his divorced daughter and recently bereaved granddaughter (her boyfriend never came back from Iraq) lie, presumably sleeping, as August Brill (for 'tis his name) makes up a story about a young man who wakes up in a hole to find that the USA is at war with itself. In the alternate universe that Brill made up for him, 9/11 never happened and instead the repercussions of the 2000 election led to full-blown civil war between the liberal coast states and conservative (not to mention much better armed) middle America. The young man is told that only he can …

A recently widowed writer, whose name by pure chance sounds a lot like "Paul Auster", lies on his back in a dark room. A car accident has temporarily disabled him, and so now he spends his nights sleepless on his daughter's couch in Vermont, telling himself stories to pass the time. Upstairs, his divorced daughter and recently bereaved granddaughter (her boyfriend never came back from Iraq) lie, presumably sleeping, as August Brill (for 'tis his name) makes up a story about a young man who wakes up in a hole to find that the USA is at war with itself. In the alternate universe that Brill made up for him, 9/11 never happened and instead the repercussions of the 2000 election led to full-blown civil war between the liberal coast states and conservative (not to mention much better armed) middle America. The young man is told that only he can stop the war. How? Kill the old bastard who's lying on a couch in Vermont making it all up.

Stories within stories, obvious author avatars, seemingly random accidents that throw an entire life out of whack, metaphysical ruminations on how we create our own world... everything is business as usual in the country of Austeria, right?

Well, maybe not. I've been wanting Auster to get back to this kind of willfully too-cleverly metafictional and yet gripping stories he used to do so well; his last two novels - the pleasant but rather pointless Brooklyn Follies and the ridiculously navelgazing Travels In The Scriptorium - had their good sides, but where one had very little for Auster fans to enjoy and the other had very little for anyone who's not a complete Austroholic, in Man In The Dark he manages to get the balance back.

So why don't I love it?

I really should. It's a very clever book. The various storylines - and boy, does he manage to pack a few into less than 200 pages - continuously refer back to the same dead objects and dead people that the novel's characters discuss in their analyses of movies; like his last two novels (and like his wife Siri Hustvedt's excellent The Sorrows of an American), 9/11 and the mad decade that's followed it remain an almost unspoken absence in the centre, just like Brill's and his granddaughter's grief is held off until the very end. It's all about how to get through without losing yourself, how to survive that private/public civil war without one side crushing the other but by finding a way to keep going. Also, this is arguably that rare beast: an Auster novel where nothing happens by chance. The setup, with our narrator incapacitated following a car accident, looks like one - until he retraces his steps and realizes what brought him here, and suddenly nothing looks random anymore. It's a trick that carries a double edge, though, since that's exactly what his granddaughter does too - and ends up with a conclusion that almost destroys her, that everything is her fault. When Brill throws his writer's quill in frustration, it's both an acknowledgement of how useless mere Story can seem (the bookstores and TV stations in New York and LA are no match for bombs, an against-all-odds love story doesn't stop cancer) and one a powerful restatement of how indespensible it is in knowing who we are. Because obviously, even when Brill gives up his attempts at fiction, Auster continues his. And as long as he does, this preposterous world keeps a-spinning.

So why don't I love it?

In a lot of ways, this is probably both the key to Auster's latest couple of efforts and to whatever is to come; a reboot. He has taken apart his fiction machine, polished and reconditioned each part individually, and then put them back together into something similar to the old one but with some new features. And that I love. But I expect a lot of Auster, and there's still some bugs to work out. Man In The Dark is a very nice novel, but it doesn't soar, damnit. When I reach the end it feels like it's not done; it's too short, too sprawling, with ideas and substories that barely have time to develop into anything but an obvious illustration of his theme before he ditches them; as if he suddenly has so much to say he can't figure out where to start or end. That gives me a lot of hope for his future novels, but for this particular one, I can't really love it.

Björn betygsatte Att hata allt mänskligt liv: 2 stjärnor

Att hata allt mänskligt liv av Niclas Lundkvist

Att hata allt mänskligt liv är Nikanor Teratologens återkomst som skönlitterär författare.

Från en värld befolkad av Morfar, Pyret …

Björn betygsatte Sleepwalking land: 4 stjärnor

Björn recenserade The Graveyard Book av Neil Gaiman

None

4 stjärnor

I really enjoyed this. Being a YA novel it's more Coraline than Sandman or American Gods, but Gaiman's YA novels are anything but infantile and there's a lot to like here.

A baby is the only survivor when his entire family is murdered by a mysterious assassin. The toddler somehow winds up in a graveyard, where he's adopted by the locals (ghosts, a vampire, various spirits), named "Nobody" (Bod for short) and raised by them as one of their own. At first, it's all rather sweet and harmless. But as he grows older, both his past and his future - he's a human boy, after all - start pulling him in a different direction from his family. They're dead, after all, and he has to learn what it means to live.

The obvious influence is Kipling's Jungle Book - it's so obvious that Gaiman even admits it - and since …

I really enjoyed this. Being a YA novel it's more Coraline than Sandman or American Gods, but Gaiman's YA novels are anything but infantile and there's a lot to like here.

A baby is the only survivor when his entire family is murdered by a mysterious assassin. The toddler somehow winds up in a graveyard, where he's adopted by the locals (ghosts, a vampire, various spirits), named "Nobody" (Bod for short) and raised by them as one of their own. At first, it's all rather sweet and harmless. But as he grows older, both his past and his future - he's a human boy, after all - start pulling him in a different direction from his family. They're dead, after all, and he has to learn what it means to live.

The obvious influence is Kipling's Jungle Book - it's so obvious that Gaiman even admits it - and since we know that story and others like it, the plot gets a bit predictable; but even then, Gaiman keeps my interest. Like Coraline it's a darker story than most writers would want to put a child in, which I like, but above all it's the world Gaiman creates around his characters. There's roots here, subtly reaching both into other stories and into the past, grounding the story in - or rather, just beside - the real world that we all live in and making the characters real with it. Gaiman borrows from others, but he borrows because he knows how the originals work and how he can make it work for him. Much like the central character, Nobody, learns to do; a name both fitting (no history, no human connections, no knowledge of how the world works) and increasingly ill-fitting as he learns and grows and pieces together his world.

"Someone killed my mother and my father and my sister."

"Yes. Someone did."

"A man?"

"A man."

"Which means," said Bod, "you’re asking the wrong question."

Silas raised an eyebrow. "How so?"

“Well,” said Bod. "If I go outside in the world, the question isn’t ‘who will keep me safe from him?’"

"No?"

"No. It’s ‘who will keep him safe from me?’"

And the answer, of course, is Nobody.

Björn betygsatte Det går an: 5 stjärnor

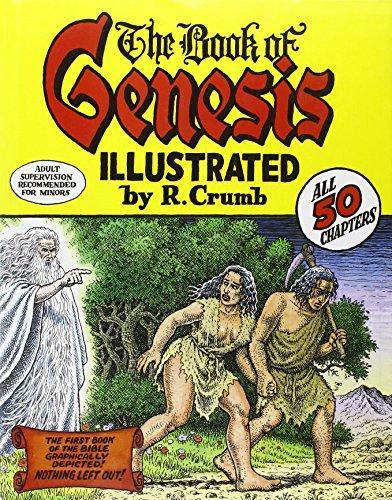

Björn betygsatte The Book of Genesis: 4 stjärnor

The Book of Genesis av Robert Crumb

From Creation to the death of Joseph, here is the Book of Genesis, revealingly illustrated as never before.

This …

Björn recenserade Rid i natt av Vilhelm Moberg

None

4 stjärnor

Spring, 1650. The thirty years' war has been over for just over a year after wiping out an entire generation of men who were sent to Germany to fight. On a small farm in Småland in the woods of southern Sweden, a widow and her newly grown son are trying to eke out a living; but even in the best of times it's a hard life, and the crops failed last year. The entire village is starving, the clothes hang empty off their backs. Which leads to problems when the local (and German) nobleman buys up the taxation rights from young Queen Christina and declares that if the farmers cannot pay in cash or kind, he'll simply a) take their farms, and b) make them work on his fields instead. The farmers protest; this isn't the continent, they say. We don't have serfdom here, we own this land, we've worked …

Spring, 1650. The thirty years' war has been over for just over a year after wiping out an entire generation of men who were sent to Germany to fight. On a small farm in Småland in the woods of southern Sweden, a widow and her newly grown son are trying to eke out a living; but even in the best of times it's a hard life, and the crops failed last year. The entire village is starving, the clothes hang empty off their backs. Which leads to problems when the local (and German) nobleman buys up the taxation rights from young Queen Christina and declares that if the farmers cannot pay in cash or kind, he'll simply a) take their farms, and b) make them work on his fields instead. The farmers protest; this isn't the continent, they say. We don't have serfdom here, we own this land, we've worked these farms as free men since heathen days. But the nobleman's henchmen (he himself never bothers to show up, of course) have guns and swords, the farmers fail to organise in time, and their alderman decides that it's better to live than die fighting. And all agree to give up their freedom - all but one, the widow's young son, who takes his gun and runs into the woods, as rumours of rebellion start to spread throughout the land...

Ride This Night! has an exclamation point in its title; it's a book that kicks off right away and then stays page-turningly urgent throughout, its prose archaically terse and grim. While the plot is centered around a few characters - the alderman, his daughter, the young partisan, the local self-styled Robin Hood, the hangman - who all get their fair due of character development, through it all runs a current of desperation and righteous indignation. Which obviously has to do with the time it was written in. There's a reason (though it's historically correct) why the nobleman is a German, why his henchmen tend to dress in black; in 1941, when Ride This Night! was written, Poland, Norway and Denmark had been occupied by Nazi Germany. Finland was unoccupied but beaten by the Soviet Union, the Baltic states annexed, and Sweden sat there in the middle of a conflict they really wanted to stay out of. And so they did what they could to placate everyone. Hitler wants to use Swedish railways to transport soldiers to Norway? Sure! Hitler wants to buy steel? But of course! And let's not complain too loudly about what's happening around us, let's just do whatever is easiest to stay out of trouble right now even if it means having to sleep badly. Like the alderman tells his farmers to do in Moberg's novel; keep your heads down, do this now even if your conscience objects, and surely things will get better eventually.

In a way, that's both the book's strength and its weakness. 70 years on, we've seen the metaphorical Nazi bad guys in everything from historical novels to sci-fi movies, and while Moberg keeps the story firmly anchored in the 17th century, the parallels are occasionally a bit too obvious - as are some of the speeches by the characters, which sometimes almost approach Red Dawn pathos (OK, obviously it never gets that bad, and it's subverted by the superb ending anyway). While it's clear where Moberg's sympathies lie - the book is a furious rally cry against complacency - he never lets any one character become a hero; he knows that simply declaring war on vastly superior powers is suicide, and the alderman's cowardice never makes less than perfect sense even if it eats him up from inside. And for the most part, he keeps the allegory just vague enough to still be relevant even after 1945. It's easy to not worry when the world grows dark around you; to simply sit back, not do your bit, wait for it to get better. And Moberg's novel calls not first and foremost for armed resistance, but for awareness, refusing to stand by and look away from injustice. And through it all, it keeps pounding the same refrain: A fiery cross is moving, the message spreads from village to village, don't let it stop, don't refuse to do your bit, ride yourself or send someone to ride for you, but keep it going, don't hesitate a second. Ride, ride this night.

Björn recenserade Perdido Street Station av China Miéville (New Crobuzon, #1)

None

3 stjärnor

I'm not sure what to make of Perdido Street Station. Like the city of New Crobuzon itself, it's built on the corpse of something that came before, and it's bursting at the seems with content but not all of it is all that enjoyable.

For starters, Miéville certainly sets himself a vast task: to create an entire new (well, not THAT new) type of fantasy world, without all the storytelling clichés of the old one - or rather, not in recognisable form. He mixes odd bits of fantasy, sf, steampunk, social realism, hard-boiled noir and silly swordplay as if he's deliberately trying for a fractured image; post-modern fantasy, a jumble where everything has been co-existing for centuries until nobody's sure where one thing ends and another begins, where you recognise the individual puzzle pieces ("One doesn't simply walk into the Glass House", indeed) but supposedly get to see them in …

I'm not sure what to make of Perdido Street Station. Like the city of New Crobuzon itself, it's built on the corpse of something that came before, and it's bursting at the seems with content but not all of it is all that enjoyable.

For starters, Miéville certainly sets himself a vast task: to create an entire new (well, not THAT new) type of fantasy world, without all the storytelling clichés of the old one - or rather, not in recognisable form. He mixes odd bits of fantasy, sf, steampunk, social realism, hard-boiled noir and silly swordplay as if he's deliberately trying for a fractured image; post-modern fantasy, a jumble where everything has been co-existing for centuries until nobody's sure where one thing ends and another begins, where you recognise the individual puzzle pieces ("One doesn't simply walk into the Glass House", indeed) but supposedly get to see them in different contexts. The story feels lived in, which is a great accomplishment. It towers, impressively.

Then again, towers in fantasy stories tend to come down, don't they?

For starters, you'd think a city teeming with life in many different sentient forms - humans, insectoids (with hot female bodies, for some reason), amphibians, plants, robots, giant extra-dimensional spiders and pretty much everything you can conceive of - would suffer from the tower of Babel issue: languages mixing, changing, characters having trouble understanding each other, etc. Well, Miéville skips right past that and has pretty much everyone speak English in translation, which, fair enough. It's worked for better writers. But then he achieves that alienation towards the reader instead, by writing the whole thing in a verbose, thesaurus-abusing prose that doesn't make him sound half as smart as he seems to think - quite the opposite, in fact. Like Stewart notes above, he consistently uses the same few Big (or just odd) Words, not to add variation, but seemingly just to show off his typing skills.

Which is a bit of a pity, because if you can slog through the endless descriptive mess of 5-syllable synonyms for "stuff China thinks sounds cool", there's both interesting characters and interesting plots to be found here, and... ah, yes, the plots. Plural. There's the wingless birdman who's looking for a way to fly. There's the scientist/magician who promises to help him. There's the scientist's girlfriend (a bug) who's given a commission to spit out (don't ask) a sculpture of a crime boss. There's the corrupt mayor and his secret police force. There's the shat-upon dock workers. And that's before we get to the dream-eating moths, and the Hell embassy, and the parasites, and the household robots plotting to take over the world, and the band of adventurers, and the stories of previous wars that lay waste to entire countries, and the endless intra- and inter-species issues, and ampersand after ampersand... any two of these plots could have filled a good book, but Miéville needs to put them all in there. Which in a way I rather like, since nothing should ever be simple in a megacity, but since he seems unable to focus, the end result is that some of the things he spends dozens of pages setting up tend to either get forgotten (presumably, left for a sequel) or tied up much too suddenly at the end. Every time you feel like you have a handle on the story, Miéville tosses in a brand-new (though derivative) mythological concept, a brand-new (though derivative) character, an entire brand-new (though derivative) plot, and when he's still doing this 3/4 into a rather thick novel it starts to get silly. It's too much, and not in a good way. I start to imagine New Crobuzon more as Ankh-Morporkh than the grimy, dark, Very Serious city its author seems to think it is.

I liked Perdido Street Station, for all its faults. I liked the characters. I liked the description of the city, at least the first 12 times or so. As a 300-page novel about the lives and politics of the inhabitants of New Crobuzon, it might have been a masterpiece. At more than twice that, filled with plots we've seen in different contexts before, and padded endlessly, it's still an interesting read, but you wonder what kind of hell-beast ate his editor's mind.

Björn recenserade Nervous conditions av Tsitsi Dangarembga

None

4 stjärnor

Gratitude. That's one of the clearest, and most double-edged, themes running through Tsitsi Dangarembga's 1988 debut, often voted one of the greatest African novels of the 20th century. And even if I don't completely agree that it is, I can see why others would think so.

Nervous Conditions is set in late-1960s and early-1970s Rhodesia, narrated by a woman named Tambudzai (though supposedly based on Dangarembga's own experiences) telling about her teenage years, starting with the day her brother dies. This, to Tambudzai, is almost a cause for celebration; not just because her brother is a complete brat who has tormented her (and gotten away with it, being the only boy in the family) for most of their lives, but because this means that she, as the oldest remaining child, will get to go to school despite being a... shudder... girl. After all, she's supposed to get married in a …

Gratitude. That's one of the clearest, and most double-edged, themes running through Tsitsi Dangarembga's 1988 debut, often voted one of the greatest African novels of the 20th century. And even if I don't completely agree that it is, I can see why others would think so.

Nervous Conditions is set in late-1960s and early-1970s Rhodesia, narrated by a woman named Tambudzai (though supposedly based on Dangarembga's own experiences) telling about her teenage years, starting with the day her brother dies. This, to Tambudzai, is almost a cause for celebration; not just because her brother is a complete brat who has tormented her (and gotten away with it, being the only boy in the family) for most of their lives, but because this means that she, as the oldest remaining child, will get to go to school despite being a... shudder... girl. After all, she's supposed to get married in a couple of years, what good is an education going to do her? But her rich uncle, educated in England ("a good boy, cultivatable, in the way land is, to yield harvests that sustain the cultivator") insists: after all, he's an enlightened African and knows that women are supposed to achieve a certain level of education so as to better serve their husbands. Just as long as she recognizes the enormous favour he's doing her, and that she never forgets that she needs to be humble and grateful for this - just like her alcoholic father is grateful towards his brother for all the times he's bailed him out of debt, like her worn-out mother is grateful towards her husband for marrying her even if he sleeps around on the side, like her uncle is grateful towards the white men for allowing him to learn how to be as civilized as they are... the word rights is, for the most part, conspicuous by its absence, and everything is always for someone else's benefit.

It might be a little simplistic to compare this to Yvonne Vera's Under The Tongue, since that's the only other Zimbabwean novel I've read. And sure, the two novels are polar opposites in some ways; where Vera loses herself in cryptic symbolic poeticisms, Dangarembga is, if anything, too literal. There are a few too many passages here where she, at least from my Western horizon, might have trusted the reader to see what she was getting at rather than spell it out and come dangerously close to sounding like a sociology textbook (Sexism in a Post-Colonial Africa: A Critical Study). And yet the story told is largely the same: the overlooked voices of girls and young women caught between a colonial power that tells them they should be grateful if they're ever treated as humans despite their race, and a traditional patriarchy (reinforced by the colonists) that tells them they should be grateful if they're ever treated as humans despite their sex. Where are they supposed to go? In both books - this one especially - the struggle for national independence is a background event, a foregone conclusion that's almost irrelevant; their own struggle has to take centre stage, especially since it's still ongoing.

The focus point of the novel - two of several very richly-drawn and complex characters - is the relationship between Tambu and her cousin Nyasha; one girl raised in a traditional home trying to fit into a Westernised system, the other raised in England and now expected to conform to traditional values - even though they live under the same roof. Neither manages to reconcile the two without giving up themselves to some degree. They're told in two languages to be grateful and subservient for what they get; but Tambu's English is as bad as Nyasha's Shona, and there's no language available to them to speak their own minds and write their own narrative.

Nervous Conditions is something of a rarity in that it's an explicitly political novel that still manages to weave its opinionating into a strong (if slightly talky) and psychologically complex narrative. Dangarembga has written a sequel, The Book of Not, which I'm sure I'll search out at some point; with Nervous Conditions, both she and Tambu take the right to be heard.

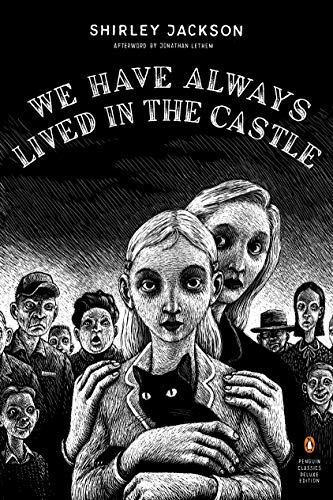

Björn betygsatte We Have Always Lived in the Castle: 5 stjärnor

We Have Always Lived in the Castle av Shirley Jackson

Shirley Jackson’s beloved gothic tale of a peculiar girl named Merricat and her family’s dark secret

Taking readers deep …

Björn betygsatte Aunt Safiyya and the Monastery: 3 stjärnor

Björn recenserade Queen Pokou av Véronique Tadjo

None

4 stjärnor

The story so far:

In the early 18th century - this must be far back enough to at least semi-qualify as "myth" in official Western history, since wikipedia says that the history of Cote d'Ivoire is "virtually unknown" before 1893 - the country was torn apart by civil war after a dispute over the throne. After having her entire family murdered, Queen Pokuaa or Pokou led her people to a new country, in the process sacrificing her newborn son to the gods so that they might cross a river and escape the soldiers chasing them down. She threw the child in the river, the river parted before them, and the new kingdom was named Baoulé after her cry: "The child is dead!"

And if that story wasn't already familiar-sounding enough, Tadjo transliterates her first name as Abraha.

Reine Pokou: Concerto Pour Un Sacrifice (Queen Pokou: Concerto for a Sacrifice) is …

The story so far:

In the early 18th century - this must be far back enough to at least semi-qualify as "myth" in official Western history, since wikipedia says that the history of Cote d'Ivoire is "virtually unknown" before 1893 - the country was torn apart by civil war after a dispute over the throne. After having her entire family murdered, Queen Pokuaa or Pokou led her people to a new country, in the process sacrificing her newborn son to the gods so that they might cross a river and escape the soldiers chasing them down. She threw the child in the river, the river parted before them, and the new kingdom was named Baoulé after her cry: "The child is dead!"

And if that story wasn't already familiar-sounding enough, Tadjo transliterates her first name as Abraha.

Reine Pokou: Concerto Pour Un Sacrifice (Queen Pokou: Concerto for a Sacrifice) is a remarkable little 90-page novella. Tadjo starts off by telling the above story in detail over the first 30 pages, giving us the main theme, as it were. Then she picks up her metaphorical tenor sax and starts playing different variations on it; what if, what if, what if? Does it make a difference how everything happened, why it happened, and what happened afterwards? What if the queen went insane from grief? What if the queen said "fuck it" to her people and tried to save her son? What if she refused the sacrifice and stayed to fight? What if they were captured and shipped off to America as slaves? What if they settled in their new home and tried to build a new culture based on the death of an innocent child? Etc etc etc. Change a detail and the entire story takes on a new meaning, from fairytale to all too realistic misery; change every detail and the basic story - a parent sends their only child into death for the sake of an uncertain future - still remains.

The parallels to child soldiers and the wars and political unrest that have torn across Africa are obvious, yet never heavy-handed. In Reine Pokou, Tadjo spins a tale that sketches out both the reasons and the results of the situation, and how interpretations of a foundation myth can make all the difference to who we think we are and should be. And her light touch and poetic language, and the suggestions that things could go differently, only makes it more brutal.

Fact-based fiction as a subjunctive clause.

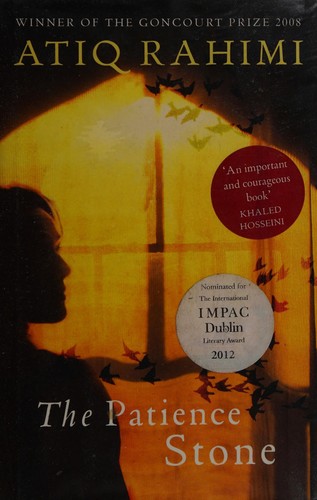

Björn betygsatte The patience stone: 4 stjärnor

The patience stone av Atiq Rahimi

In Persian folklore, Syngue Sabour is the name of a magical black stone, a patience stone, which absorbs the plight …